Pěkné čtení.

KNIGHT'S ARMOUR (11TH - 15TH CENTURY)

Categories: What didn't fit elsewhere

Knights used various weapons: spear, crossbow and bow. In man-to-man combat, they used the axe, mace, and especially the sword. But the knights' favourite weapon remained the lance. In "historical" works such as the chronicles, as well as in literature, the sword is drawn only when the spear is broken.

There are several surviving examples of swords dating from the 11th and 12th centuries that served the knights of William the Conqueror, the first crusaders, the rivals of Roland and Olivier. Such a sword measured 90-100 cm and weighed 1 -1.8 kg. The double-edged sword had a central groove in its part, which made it lighter but did not reduce its durability. At the end of the hilt, made of wood, horn or bone, covered with leather or twine to make it easier to hold in the hand, was a round knob (pear) whose purpose was to ensure the balance of the weapon. It sometimes contained relics, such as Durendal, the sword of the main character in the Song of Roland.  Knights often gave their swords names, like horses, to show their affection for a weapon from which they could rarely separate themselves. Some swords were adorned with instructed inscriptions, in gold or silver, or just engraved on the blade. These may have been insignia of the owner, more often the name of the maker, or possibly formulas of a religious nature, which probably served as talismans. According to the historian and blacksmith S. Peirce, it took about 200 hours of work to make such a weapon, far more time than to make a thigh-length wire shirt called a hauberk.

Knights often gave their swords names, like horses, to show their affection for a weapon from which they could rarely separate themselves. Some swords were adorned with instructed inscriptions, in gold or silver, or just engraved on the blade. These may have been insignia of the owner, more often the name of the maker, or possibly formulas of a religious nature, which probably served as talismans. According to the historian and blacksmith S. Peirce, it took about 200 hours of work to make such a weapon, far more time than to make a thigh-length wire shirt called a hauberk.

Swords were used as weapons of cutting rather than stabbing, and heroic chants often go on at length about how strong an arm a knight had and how sharp his sword would be, capable of cutting through the body of an enemy or even... his horse! Bodily remains found sometimes show very deep wounds, severed limbs and severed bodies, although it is impossible to say for sure whether these were caused by a sword or an axe. The use of battle-axes and maces, attested from the 11th century especially in England, became widespread in the 14th century. century and even more so in the 15th century, in parallel with the introduction of the great two-handed sword, a time when weapons were becoming larger.

The short and thin-bladed dagger (20 cm), later called the "merciful"...was used to overpower the defeated or to intimidate him into surrendering. The dagger could also be plunged into a solid part of the shell. From the 11th to the 13th century, sword fighting often followed the first attack using a spear, both in war and in tournaments.

The short and thin-bladed dagger (20 cm), later called the "merciful"...was used to overpower the defeated or to intimidate him into surrendering. The dagger could also be plunged into a solid part of the shell. From the 11th to the 13th century, sword fighting often followed the first attack using a spear, both in war and in tournaments.

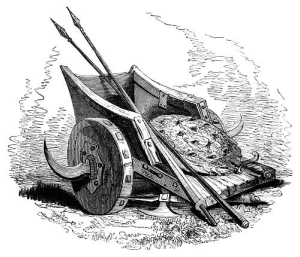

The spear, which is named in Latin texts as hasta or lancea and in French as lance, espié or glaive, remained the characteristic weapon of the knight throughout the Middle Ages. Until the 11th century it was used as a stabbing weapon and measured less than 250 cm. It became longer and heavier after a new form of attack with the outstretched spear took hold and became widespread, reaching 350 cm in length during the 13th century and later becoming even longer. In the early 14th century it weighed 15-18 Kg. The ash, apple or beech wood spearhead was sometimes preceded by a double-edged pointm was decorated with an elongated triangular flag or a coat of arms or a flag indicating the position of the person carrying the spear. The knight - the lord of the standard commanded a group of knights, called conroi. The pennant or banner, a symbol of command, served as a landmark in battle. A lance bearing the coat of arms could also be used as an offensive weapon in the new technique of combat, thus precluding its original focus as a throwing weapon. To prevent the point from penetrating too deeply and then not being able to be pulled back out of the body, a bump or flange was placed on it. In parallel with the lengthening of the spear and the increase in its weight, its grip had to be addressed. It was fitted with a circular shield at the end of the hand that held it to cushion the recoil, at the end of 14. In the early 15th century, a safety stop (rake) was placed on the knight's shell, which came into general use in the early 15th century. It was a kind of fixed hook on the armour that allowed the spear carriage and the carapace to be brought into line, and to relieve the weight of the spear. The usual technique was to hold the spear with the right arm and guide it obliquely in the direction of the opponent, i.e. forward somewhat to the left above the horse's neck. The shield was therefore also held by a slight deflection to the left, in the direction of the intended attack. Also, the armour used in matches and tournaments was soon asymmetrical, reinforced in the left part. Because the blow was lethal, blunted spears were used in some "fun" matches and tournaments from 1200 onwards: The tip was replaced by a notched crown, which was intended to allow an opponent to be thrown out of the saddle without stabbing the attacker.

In parallel with the lengthening of the spear and the increase in its weight, its grip had to be addressed. It was fitted with a circular shield at the end of the hand that held it to cushion the recoil, at the end of 14. In the early 15th century, a safety stop (rake) was placed on the knight's shell, which came into general use in the early 15th century. It was a kind of fixed hook on the armour that allowed the spear carriage and the carapace to be brought into line, and to relieve the weight of the spear. The usual technique was to hold the spear with the right arm and guide it obliquely in the direction of the opponent, i.e. forward somewhat to the left above the horse's neck. The shield was therefore also held by a slight deflection to the left, in the direction of the intended attack. Also, the armour used in matches and tournaments was soon asymmetrical, reinforced in the left part. Because the blow was lethal, blunted spears were used in some "fun" matches and tournaments from 1200 onwards: The tip was replaced by a notched crown, which was intended to allow an opponent to be thrown out of the saddle without stabbing the attacker.

Knights' armour evolved in response to increasing offensive power. Only from the mid-11th century onwards. century, when a new attacking technique emerged, the warrior's body was protected by a scaly short skirt with a slit, worn over a leather tunic, or skirt-shaped chain mail that reached mid-thigh. From the mid-11th century to the mid-13th century, the use of the ring tunic or hauberk became universal. It extended in length and its slit was intended to allow the knight to swing himself up on his horse, with both ends of the skirt protecting his thighs. No 11th, 12th or 13th century hauberk survives, but we do know of some 10th century examples. The tunic-shaped ring armour offered good protection against sword blows, but less protection against arrows and throwingspears, and even less from axes, arrows with square points from crossbows or spears during an attack. Its good quality was its flexibility and relative lightness (12 - 15 kg). This weight, though not insignificant in total, but spread over both shoulders, made it possible to move well on horseback or on foot. Each eyelet or ring was connected to four others, which held it, but at the same time gave itgiving a certain freedom, so that the result was a fairly flexible garment, the more effective because the rings were fine and numerous. It is estimated that a single hauberk may have consisted of 20,000 to 200,000 interlocking rings. The impact energy was thus spread over a larger area. Further cushioning of the blow was to be achieved by a padded coat or varkoch or gambeson (gamboison) worn under the hauberk to prevent painful injuries. There are also opinions that the hauberk did not protect (like the so-called haubergeon, a sleeveless wire shirt up to mid-thigh) only the head and shoulders, but the whole body. Other protective parts were added: short pleated trousers made of metal rings, fingerless gloves, which became widespread during the 12th century. The wire cap, which was worn under the helmet and protected the head in the 11th and 12th centuries. Around 1150, knights wore a cape over their hauberk, adorned with their heraldic emblems, by which they recognised themselves and which reinforced their solidarity and the knightly 'superiority complex'.

Knights' armour evolved in response to increasing offensive power. Only from the mid-11th century onwards. century, when a new attacking technique emerged, the warrior's body was protected by a scaly short skirt with a slit, worn over a leather tunic, or skirt-shaped chain mail that reached mid-thigh. From the mid-11th century to the mid-13th century, the use of the ring tunic or hauberk became universal. It extended in length and its slit was intended to allow the knight to swing himself up on his horse, with both ends of the skirt protecting his thighs. No 11th, 12th or 13th century hauberk survives, but we do know of some 10th century examples. The tunic-shaped ring armour offered good protection against sword blows, but less protection against arrows and throwingspears, and even less from axes, arrows with square points from crossbows or spears during an attack. Its good quality was its flexibility and relative lightness (12 - 15 kg). This weight, though not insignificant in total, but spread over both shoulders, made it possible to move well on horseback or on foot. Each eyelet or ring was connected to four others, which held it, but at the same time gave itgiving a certain freedom, so that the result was a fairly flexible garment, the more effective because the rings were fine and numerous. It is estimated that a single hauberk may have consisted of 20,000 to 200,000 interlocking rings. The impact energy was thus spread over a larger area. Further cushioning of the blow was to be achieved by a padded coat or varkoch or gambeson (gamboison) worn under the hauberk to prevent painful injuries. There are also opinions that the hauberk did not protect (like the so-called haubergeon, a sleeveless wire shirt up to mid-thigh) only the head and shoulders, but the whole body. Other protective parts were added: short pleated trousers made of metal rings, fingerless gloves, which became widespread during the 12th century. The wire cap, which was worn under the helmet and protected the head in the 11th and 12th centuries. Around 1150, knights wore a cape over their hauberk, adorned with their heraldic emblems, by which they recognised themselves and which reinforced their solidarity and the knightly 'superiority complex'. Literary texts often refer to double or triple hauberks. The question is how to understand these documents. Did they suggest a tighter interlocking of more rings, or a reinforcement of the layers due to the rings being much finer? Or was it a partial strengthening of the hauberk, for example on the chest? As a rule, we refuse to imagine the possibility of a knight wearing two hauberks on top of each other, and are inclined to think that this information is chargeable to the epic sweep of the authors. The Syrian nobleman Osama in the 12th century nevertheless performed in such garb, and his example is not considered exceptional. Understandably, we question the weight of the armour he had to bear. Perhaps they were very fine rings?

Literary texts often refer to double or triple hauberks. The question is how to understand these documents. Did they suggest a tighter interlocking of more rings, or a reinforcement of the layers due to the rings being much finer? Or was it a partial strengthening of the hauberk, for example on the chest? As a rule, we refuse to imagine the possibility of a knight wearing two hauberks on top of each other, and are inclined to think that this information is chargeable to the epic sweep of the authors. The Syrian nobleman Osama in the 12th century nevertheless performed in such garb, and his example is not considered exceptional. Understandably, we question the weight of the armour he had to bear. Perhaps they were very fine rings?

From the 13th century onwards, protective armour became heavier. The wire tunic was reinforced in exposed areas (chest, arms, back) with plates of metal or boiled leather. It was a plate armour, which covered the tunic with rings of increasingly numerous, wide and thick rings until 1350. It offered better protection from blows and shots. It represented a reinforced armour, although heavier, but its maintenance was easier than that of the hauberk, which had to be regularly "rolled" and anointed with oil to prevent rust from reducing its elasticity. In the mid-14th century, armour called 'proved' effectively protected against bow shots, not crossbow shots. Yet the wire shirt did not disappear. It was often used under a shell or as light armour. At the end of the development in 15. the great "iron" armor, armor composed of solid articles ofparts that offered maximum protection at the cost of increased weight.

Improvements in armour also included headgear and shields. In the 11th and 12th centuries, the Norman model prevailed: a beam was added to the "helmet", a conical helmet of riveted strips that often did not cover the entire head, and in the late 12th century, the "helmet" was added to the "helmet". In the 12th century, a camouflaged face cover was added to protect the face, especially from sword thrusts from above. The helmet was worn on top of a cap of wire loops, which was used to gather the hair above the top of the head at a time when fashion favoured long hair or a forelock. In the 13th century, the helmet was supplemented by a closed cylindrical 'pot helmet' with narrow eye-holes, which provided better protection but limited visual and auditory perception. Especially in the southern regions, it had to be fitted with sufficiently large openings for air intake. Protective elements and various ornaments were added to the helmet: a heraldic chochol, a batvat, a shishak, etc. All this increased its weight, so it was abandoned in the mid-14th century and replaced by a helmet with a movable visor.

Among the variously shaped shields, it dominated in the 11th and 12th centuries. The Norman model was a wooden shield covered with leather, pointed at the bottom, and shaped like an almond with a strongly arched bulge. In the 12th century, heraldic emblems were added. It protected the body well, but it could not withstand the strong penetration of an outstretched spear. With the discovery of plate armour in the 13th century, a small shield, first rectangular and then of various forms, was preferred at the beginning of the 14th century. in the early 17th century, a cut-out was added to allow the spear to be held. The introduction of armour reinforced on the left replaced the shield, which disappeared in the 15th century. The knight was armoured from head to toe: he wore short pleated trousers and knee breeches, iron gloves and shoulder pads, and a large helmet with a visor on his head.

We have become accustomed to the distorted image of a knight invincible on horseback but unable to move on his own two feet. This image has been refuted by literature itself, presenting us with knights thrown from the saddle, often ending their struggle as foot soldiers, sword or axe in hand. It must be remembered: the weight of the armour allowed such an approach. The Hauberk was about 12 Kg, which was certainly a considerable load, but its distribution over the entire body of sturdy and well-trained knights allowed them to move. Boucicaut (a French marshal who served John II and Charles V) at the end of the 14th century. century confirms that, thanks to his physical training and therefore strength (he could climb a ladder with the strength of one arm), he was able to jump onto a horse in full armour. Only the armour designed for tournament jousting, which was very massive and asymmetrical, reached a weight of 50 Kg, even 70 to 80 Kg, making any other way of fighting impossible. War armour also intensified in the 16th and 17th centuries, when it was (vainly) looked to for protection against small arms.

Horses, the privileged targets of archers, were protected by "blankets" from the 12th century onwards, and in the 13th. and 14th centuries of wire rings or boiled leather, and real armour in the 15th-16th centuries. They wore a metal headdress. Headdresses and armour for horses led to ever longer spurs. Of course, a knight had to own a riding animal, preferably two, later five or six warhorses. (destriers), and one, usually two servants, who had the duty of carrying his weapons, looking after the horses and making sure they were replaced in case the knight lost a horse: under Duke William, three horses died at Hastings. The animals intended for the battlefield had to be powerful and were supposed to be a kind of intermediate stage between cavalry and draught horses: they were required to be fast and sturdy, trained for attack and battle. To fight in the saddle of a mule, or even worse a parade or ladies' horse - a palefroi, a draught horse or a soumara - meant great humiliation for the knight, which unfortunately the less well-off could not avoid. The knight also had to have grooms to look after the horses and armed servants. For example, the Treaty of Alton (Douvres) of 1101 between Robert II, Count of Flanders, and Robert II of France. and King Henry of England stipulated that every Flemish knight entering the service of the English king should bring with him two men-at-arms and three warhorses. The way of life of the knights depended, of course, on their social status, but unless the lowest-ranking knight was supported by his lord, he must have had considerable means at least to acquire the necessary equipment.

Horses, the privileged targets of archers, were protected by "blankets" from the 12th century onwards, and in the 13th. and 14th centuries of wire rings or boiled leather, and real armour in the 15th-16th centuries. They wore a metal headdress. Headdresses and armour for horses led to ever longer spurs. Of course, a knight had to own a riding animal, preferably two, later five or six warhorses. (destriers), and one, usually two servants, who had the duty of carrying his weapons, looking after the horses and making sure they were replaced in case the knight lost a horse: under Duke William, three horses died at Hastings. The animals intended for the battlefield had to be powerful and were supposed to be a kind of intermediate stage between cavalry and draught horses: they were required to be fast and sturdy, trained for attack and battle. To fight in the saddle of a mule, or even worse a parade or ladies' horse - a palefroi, a draught horse or a soumara - meant great humiliation for the knight, which unfortunately the less well-off could not avoid. The knight also had to have grooms to look after the horses and armed servants. For example, the Treaty of Alton (Douvres) of 1101 between Robert II, Count of Flanders, and Robert II of France. and King Henry of England stipulated that every Flemish knight entering the service of the English king should bring with him two men-at-arms and three warhorses. The way of life of the knights depended, of course, on their social status, but unless the lowest-ranking knight was supported by his lord, he must have had considerable means at least to acquire the necessary equipment.

How much does it cost to equip a knight?

Documentary sources often give an indication of the price of horses, but unfortunately do not specify their quality. The value of the horse and the warrior's attachment to this animal led to the development of breeding, the establishment of stud farms and advances in veterinary medicine, traces of which can be found from the 12th century onwards. The horse was an essential working tool for the knight, his main trump card, but also a companion, a friend on whom the knight's life often depended. Its death was a catastrophe for many knights, the horse was mourned and "longed for" as a close creature, It occupied a central place in the knight's mind and in contemporary literature.

Until the 9th century, a warhorse was worth about four head of cattle. Its value rose during the 11th century, when horses suitable for war were refined. The weight of such a horse exceeded 600 kg. It is thought that a horse could carry a fifth of its weight, which at the time of the Crusades meant that it could carry a knight with weapons weighing 120 Kg. A war steed (destrier) was twice as expensive as a palefroi, a horse for parades or ladies, and three times as expensive as a roncin, a draft horse. The price of horses varied according to place and circumstance: on the eve of the Crusades, it oscillated between 40 and 200 sous (Frank = 20 sous). It was equivalent to five to sixteen head of cattle or several war horses.

Around 1100, the minimum cost of knightly equipment (hauberk, helmet, sword) was therefore about 200-300 sous, which was equivalent to the cost of about thirty cattle. In the mid-13th century it was four to five times more, but taking into account the depreciation of the currency in the 12th century, this represented a significant increase in price. Nevertheless, the cost of armour and horses, and probably even more so the cost of the knighting ceremonywhich had to include the expense of the costly ceremony, led many noble families to abandon the knighting ceremony.

Around 1100, the minimum cost of knightly equipment (hauberk, helmet, sword) was therefore about 200-300 sous, which was equivalent to the cost of about thirty cattle. In the mid-13th century it was four to five times more, but taking into account the depreciation of the currency in the 12th century, this represented a significant increase in price. Nevertheless, the cost of armour and horses, and probably even more so the cost of the knighting ceremonywhich had to include the expense of the costly ceremony, led many noble families to abandon the knighting ceremony.

From 12. the English and French monarchs found it difficult to obtain knights from their vassals with completewhich they were normally expected to acquire from the fiefs they were granted (hauberk fief, knight's fief). Many knights preferred to free themselves from this obligation by paying a fee, a ransom for the 'service of a groom'. The funds thus raised enabled the princes to hire knights to fight for hire. who had their own equipment. It was the first step towards the formation of later standing armies. As the 13th century approached, only nobles whose wish was to build a career in the military profession underwent the rite of passage. This dual movement led to the emergence of mercenary troops, operating alongside the feudal conscriptionbut which remained indispensable, supplying the prince with fully equipped knights "free of charge" and saving him expense.

In the 12th century, the training of a knight, including his equipment, was equivalent to approximately the annual income of a medium-sized manor or the yield of a farm of about 150 hectares. Clearly, knights in such circumstances were not 'poor'. Yet at that time historical sources, and even more so literary works, refer to 'poor knights'and in the lower than aristocratic classes, tensions can be identified that no doubt reflect the unrest in society. It led to a defensive stance and a reinforcement of the ideological emphasis placed on the merits and privileges of chivalry. Let us recall that the word pauper does not denote a real cripple in the Middle Ages, but a person who "cannot live on his own", cannot get his needs met, cannot maintain his position. A "povre chevaler" was neither a poor king nor a poor peasant. He was a warrior whose material situation proved precarious (the blows of fate struck professional warriors so often!), it carried the risk that the knight would lose the necessary equipment he needed to "maintain his position" in the exercise of his profession. These knights were most often in a dependent position, but there were also independent knights for whom the equipment they acquired in the rite of passageand who, in times of turmoil, lived on plunder or booty gained in wars or tournaments. When the power of the princes in the 12th century established order and the power of the state, war and tournament were indispensable to their existence.

FLORI, J.: Knights and Chivalry in the Middle Ages

www.e-stredovek.cz/

http://www.boiohaemum.cz/

---

You can search for artefacts from this period using our metal detectors.

The article is included in categories:

Post

Pěkný článek !

platovou zbroj jsem vyrabel tak vim o cem pisete.je to velmi zajimava prace ale i ta historie.clovek zasne jaky to byli mistri platneri.to co dokazali oni driv,to nedokaze dnes nikdo.jenze pravda je takova ze dnes se treba obycejny salir behem dvou dnu hotovy,ale drive ho delali tydny.rika se ze drive meli kvalitnejsi mece nez dnes ale neni to pravda.mi aby jsme udelali kalitelnou ocel,tak do ni pridavame uhlik.oni takovou moznost drive nemeli.muj mistr na tuton praci rikal ze oni ty mece,aby byli tvrde tak je strkaly do praseciho hnoje.ze pry jsou tam ty vseliaky kyseliny,ale to nemuzu tvrdit ze je to pravda.....jinak je to nadherna prace........zdenek

http://www.drcbrno.cz/hmotnost-mece/